Blame This Man for Auto-Tune

It has been a long time since I’ve shared a story from my Inventor Profile series. So let me tell you about Andy Hildebrand, the inventor of Auto-Tune, the 47th inventor I interviewed for the series.

In 2014, I visited Andy at his secluded home in the hillside redwoods of the Santa Cruz Mountains, south of San Jose.

Down a little pathway from his house was a stand-alone woodshop where Andy did woodworking as a hobby to relax, spending 10 to 20 hours a week there. So that was where we did most of our interview.

Andy got his PhD in electrical engineering, but he also had a music background. He played flute for studio sessions and symphony orchestras. So in his forties, after retiring young from a company he’d started, he went back to school and studied music composition at the Shepherd School of Music at Rice University.

While at Shepherd, he was annoyed by how he could hear the repeating seams in the looping samples that their synthesizer used. He figured that with his engineering background, he could write some software to make those loops seamless. Once perfected, he started a new company called Antares Audio Technologies to sell the software.

At a trade show luncheon, a colleague’s wife mentioned that she wished there were a device that could make her sing in tune. And Andy instantly realized that he knew how to do that. It took about a year before he got to it, but soon he released the first version of Auto-Tune.

Andy didn’t quite realize how people would end up using it:

Auto-Tune has a dial called speed. For songs that are slow, you don't want to adjust the pitch rapidly. It sounds artificial. You want to adjust it slowly. For songs that are fast, a lot of words in a short time, you want to have the pitch adjust more quickly. So there's a dial to let you do that.

And I wanted to know at what speed I should let the user go. Should I let it go to an instantaneous speed or not? My director of marketing, Marco Albert, said “What's the harm in letting it go to instantaneous?” So we allowed the user to set this to instantaneous. I disagreed. I thought nobody in their right mind would ever use it that way. It created such an artificial sound.

But of course, people did. A couple years after Auto-Tune was released, Cher’s song “Believe” came out using instant pitch changes for effect. It was a new sound that caught on quickly and permeated across genres, but some people really hated it.

It more or less bifurcated the audiences. Some people liked it and some people hated it. I have been congratulated for doing a wonderful invention and helping people be in tune when they sing. And on the other hand, I have another half of the population saying that I ruined Western music.

I explain to people, I just build the car. I don't drive it down the wrong side of the freeway.

After our interview, I went with Andy to his office, where he gave me a demonstration of Auto-Tune.

At some point during the demonstration, he mentioned to me that Auto-Tune requires a hardware dongle as a measure to prevent piracy. I was surprised by this. I thought the idea of anti-piracy dongles was outdated. In the early days of digital photography, I used some professional camera control software that required a dongle, and it was a low-level annoyance.

So I told Andy that I assume pirates will always find ways to defeat that sort of thing, and it’s annoying to have something taking up a computer port just to use an app. It always seemed to me like hardware dongles just punish people who legitimately purchase software.

He disagreed, and I think he thought I was a little naïve to suggest it. I have no idea whether or not Auto-Tune still requires a dongle today.

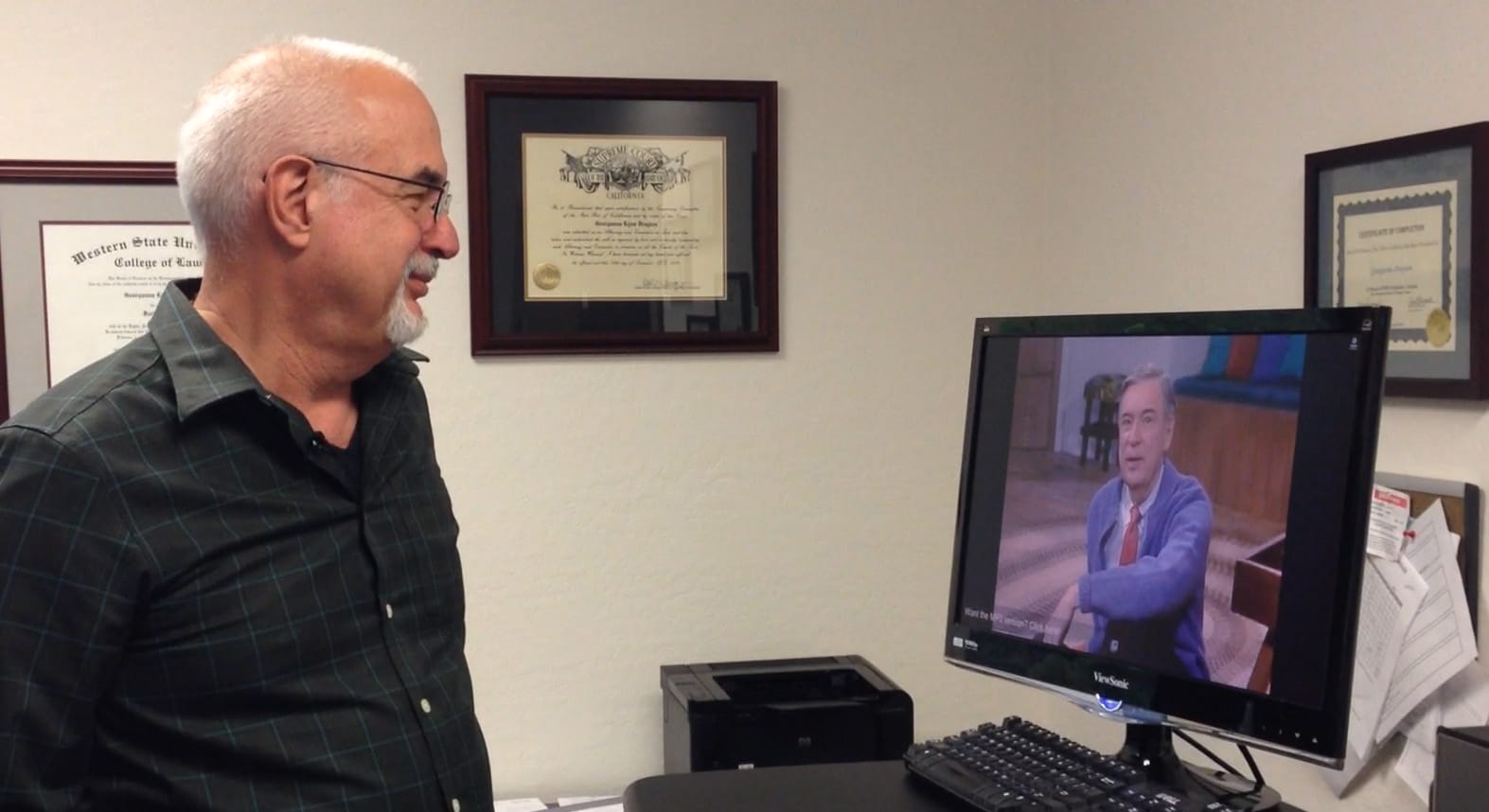

We rounded out our conversation by talking about some viral uses of Auto-Tune, like the Gregory Brothers “Auto-Tune the News” series (you may know it as the renamed “Songify the News”). And we watched together the PBS video where Mister Rogers was remixed into a song called “Garden of Your Mind.”

After gathering all my photos and footage of Andy, I thought that instead of making a straightforward documentary video about him like I did with so many other inventors, it would be funny if I did an Auto-Tuned video that tells the story of Auto-Tune, making use of my interview footage.

The only problem was that I had no idea how to do that. So I kept putting it off, thinking I would eventually find someone who does know how to use Auto-Tune and we could collaborate. But I didn’t look very hard, and weeks turned into months turned into years. Now it’s been so long that everything in my footage feels too much of-its-time. Seeing my shots of him demonstrate an old version of Auto-Tune on an old version of OS X would instantly date it. So perhaps it could work as a throw-back, but might be a bit weird to see old software in a brand new video.

I might have missed the window for making a finished video of this one. But if the Gregory Brothers happen to be reading, let’s talk!

Something I find great about Andy’s story is how much of it isn’t the cliche “Eureka!” invention moment that people think of sometimes when they think of inventors. The initial idea for Auto-Tune came from a colleague’s wife. And he not only didn’t want to allow for “instantaneous speed” but couldn’t fathom how anyone would make use of it.

It shows how invention is collaboration, and also how misusing something can sometimes be innovative.

And with that, another newsletter comes to a close. But before I sign off, I have this little problem.

A lot of times my newsletters get shared and tens of thousands of non-subscribers read it, and that’s great! But even the issues that get so widely distributed fail to translate into many new subscribers. I need to do a better job at conversion. Ghost doesn’t have as many nice tools to help with that as the other places, as far as I can tell, so I’m looking into some things I can integrate.

Meanwhile, if you’re not already a subscriber, and you made it this far, why not sign up while you’re here? It’s free!

Until next time, thanks as always for reading!

David