The King of Blurbs

“A gripping tale of hubris, hyperbole, and hardcovers!” - a famous author

Did you realize you can get this newsletter for free? You pay if you want, but you don’t have to! So if someone you know sent you here, why don’t you sign up?

You know I can’t resist a pun, so based on the title of this week’s newsletter, it would be a reasonable guess that I’m going to talk about Stephen King and how it seems like there’s no book he won’t blurb.

Back in 2008, King wrote about his blurb habit in Entertainment Weekly, saying, “I’ve lent my name to perhaps a hundred books.” He admits that his first blurb was for a book he didn’t especially like, but claims that since then “I’ve done it only for books I honestly loved.”

The year he wrote that article, a Seattle librarian noted that King described more than one book as his favorite of the year, which obviously can’t be possible. And over on Goodreads someone has attempted to crowdsource a list of all the books King has recommended in blurbs or other reviews, which seems an overwhelming challenge.

So yes, Stephen King blurbs a lot of books.

But as much as I like puns, in this case, I actually wasn’t talking about Stephen King. I meant “king” in the sense of a person who is at the top in a category. Because it turns out that, among literati, Stephen King is not the King of Blurbs. Another candidate might be A.J. Jacobs, an author who describes himself as having a “blurbing problem.” But he doesn’t get the title of Blurb King either.

That crown belongs to a guy named Gary Shteyngart.

Who the heck is Gary Shteyngart?

Gary Shteyngart is a Russian-American humor novelist who, despite having been on the New York Times bestseller list with his critically praised novels, is not a household name the way Stephen King is.

But over several years, he developed a reputation among the literary-minded as a prolific blurber. There’s no official blurb leaderboard, but if he doesn’t have the most blurbs to his credit, he’s certainly high up there.

While King said he blurbed “only for books I honestly loved,” Shteyngart had a very different criteria. He once explained to the New York Times:

“My blurbing standards are very high,” Shteyngart told me. “I look for the following: Two covers, one spine, at least 40 pages, ISBN number, title, author’s name. Once those conditions are satisfied, I blurb. And I blurb hard. I’ve blurbed about a hundred novels in the past 10 years, nearly every one that landed on my desk.

A Tumblr page (did we used to call those Tumblogs?) even sprang up attempting to chronicle The Collected Blurbs of Gary Shteyngart. A sampling of his blurbs:

Missing Kissinger by Etgar Keret

“The best work of literature to come out of Israel in the last five thousand years—better than Leviticus and nearly as funny.”

Vintage Attraction by Charles Blackstone

“If you like pugs, wine, and Greece, Vintage Attraction is for you. It’s so post-post-modern it’s almost pre-modern. I read it on a stone tablet and loved every word.”

Broken Piano for President by Patrick Wensink

“I like Patrick Wensink’s work so much my heart had to issue its own cease-and-desist order.”

Shteyngart blurbed so freely that in 2013, writer Edward Champion made a short documentary about Shteyngart and his blurbs, including interviews with many of the authors whose books he blurbed.

In the film, Shteyngart explains his exuberance, saying, “I’m trying to get people to read good serious literary fiction… no hyperbole can be hyperbolic enough.”

Turns out there was too much after all

In April, 2014, the New Yorker published an open letter from Gary Shteyngart in which he announced his retirement from blurbing.

Dear Everyone,

During the past ten years, it has been my pleasure and honor to blurb over a hundred and fifty books. It is with deep sadness that I announce that the volume of requests has exceeded my abilities, and I will be throwing my “blurbing pen” into the Hudson River during a future ceremony, time and place to be determined.

He didn’t provide a specific reason for the halt in blurbing. But he explained that he would make some exceptions, with a list of exempt categories including his current and former students, authors of his editor or agent, authors who can prove they own a long-haired dachshund, and anyone with the first name Daria.

The New York Times reported that when the news broke, “a disturbance rippled through M.F.A. programs, publishing houses and certain neighborhoods of Brooklyn.”

That sounds about right.

The blurb king is dead. Long live the blurb king.

Blurb. That’s a funny word.

I’ve written the word “blurb” so many times so far that it’s stopped looking like a real word. Blurb. I never really thought about that word before. It’s one of those words that sounds like it means, right? A blurb is just a small sentence of praise. Not a long review. Just a little thing. You know. A blurb.

But it turns out, the word blurb is named after a fictional character and was invented as a bit of a joke.

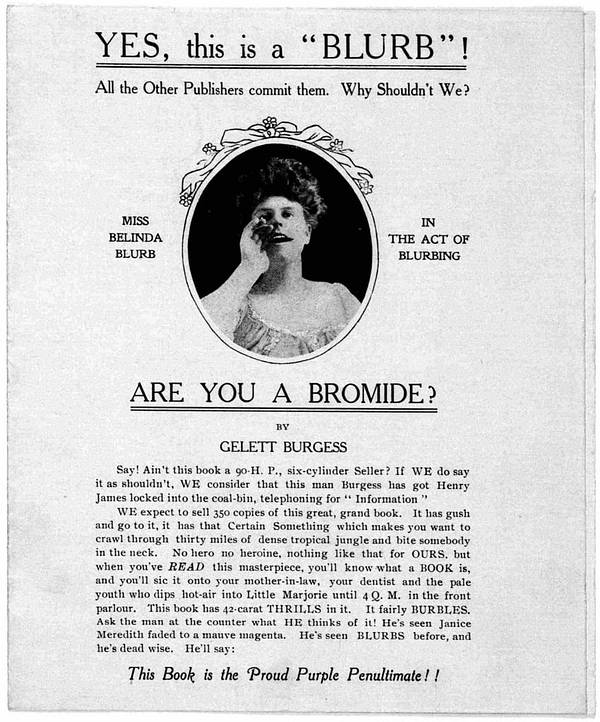

Putting promotional quotes on your book was already a practice in 1907 when a writer named Gelett Burgess published his book Are You A Bromide? But he decided to have a little fun with it for a special edition of his book. He was attending the annual dinner of the American Booksellers' Association as an honored guest, and as was customary, he brought copies of his book to give away to his colleagues.

For this special edition, he stole a photo of a woman from a dental ad and put her on the dust jacket. The photo had her posed as though she was shouting, and the image on the dust jacket was captioned “Miss Belinda Blurb in the act of blurbing.”

Below the photo was a paragraph filled with comments like, “When you’ve READ this masterpiece, you’ll know what a BOOK is,” and “it has that Certain Something which makes you want to crawl through thirty miles of dense tropical jungle and bite somebody in the neck.” Now that’s a blurb!

Burgess’s colleagues found it all so amusing that they soon made their own funny editions of their books with over-the-top quotes on them. They called these “Blurbs” in honor of the original Burgess edition.

Eventually, the word came to refer to that format of praise, whether sincere or humorous.

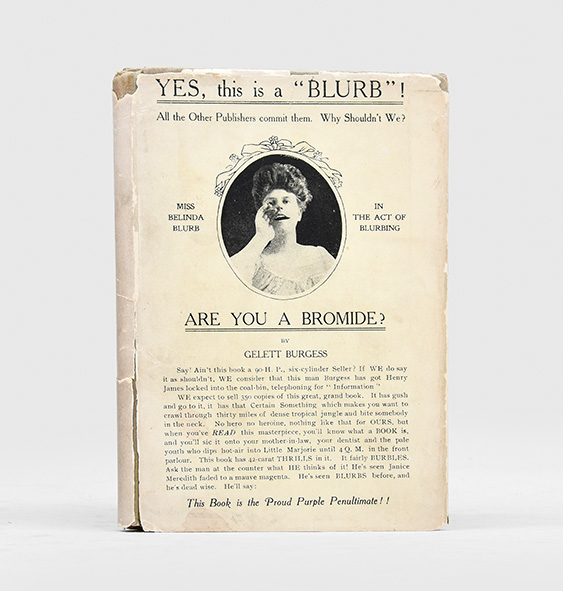

This worn copy of the very first blurb is available to purchase for $1,353.48:

The New York Times wrote about the word’s emerging popularity in 1922, observing that:

The blurb-writer, when he is truly a master of his craft, will exaggerate so cautiously and so imperceptibly that we must believe him to be uttering truth. If he forces us to be aware of his exaggeration, then are we made to doubt his qualification for uttering truth.

So keep that in mind if you’re ever asked to write a blurb.

As this newsletter comes to a close, I will note that I am currently accepting blurbs, even though I don’t have a dust jacket to put them on. But I will put them on my phone and look at them whenever I need to feel better about myself.

Maybe that should be a thing, actually. Personal Blurbs. Your friends can send in over-the-top praise just about you as a person that you keep handy for when you’re down or stuck and really need a pick-me-up. Like, “An electrifying presence in any group text.” Or, “Her PowerPoint presentations will surely earn her a place on the Pulitzer short-list.” Or “A can’t-put-down friend that you’ll bond with in one night.” That sort of thing.

And if you don’t have any friends, maybe you can manage to get a Personal Blurb from Stephen King.

Thanks as always for reading. See you next time!

David