The Optical Illusion That Let Black and White TVs Show Color

A forgotten experiment in visual perception

By the end of the 1960s, only around 31% of American households had color TVs. Black and white television was still the standard. But a guy named James Butterfield had an idea: What if you could get a black and white TV set, which completely lacks the technology required to render a color image, to show color anyway?

Amazingly, he got it to work. Sort of. It wasn’t a perfect color image like you’re used to seeing on TV. It was an effect that created an illusion of color, and didn’t work for all viewers. The effect was used in at least one commercial, amazed a lot of people, and then was mostly forgotten.

Hopefully we’re far down enough on the page that people who are sensitive to flashing have heeded the warning above, so I can safely show you what this illusion looked like:

Each frame in this image is really just black and white. But the intended effect is the word “ZiP” in red, with a green curved shape above it, and a blue shape below it. Do you see the colors?

Butterfield’s innovation was based on a weird fact about our eyesight, a phenomenon that’s still not fully understood by science. You probably know that most people have three types of color receptors in their eyes, sensitive to wavelengths of red, green, and blue. But it seems that the brain pathways for those receptors don’t all operate at the same speed.

So for example, if you were looking at a screen that just flickered black and white, the signals from your eye would reach your brain with tiny timing differences each time the screen changed from white to black or back. Maybe the red channel reacts quickly, and the blue one lags just a bit behind. So the brain gets slightly out-of-sync signals from each channel, and for just a split second, your brain interprets that mismatch as a color even though there is no actual color there.

It all happens incredibly fast, so you don’t really notice. Usually.

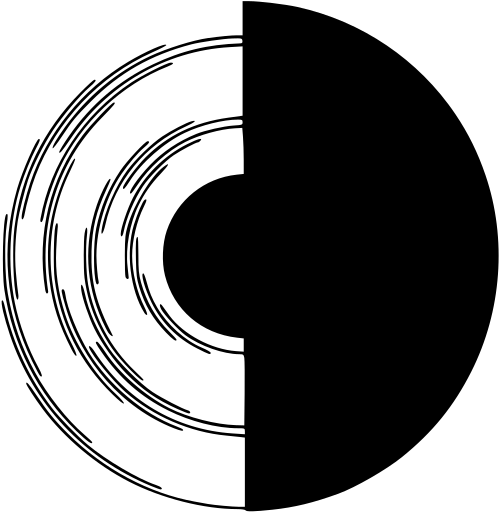

But it’s possible to deliberately trigger this phenomenon. You may have even done it yourself using a toy known as a Benham’s disk – which was originally marketed as the Artificial Spectrum Top in the late 1800s. The surface of the top looked something like this:

And when it spins, it creates a subtle illusion of color. It even works in digital form, as seen in this GIF:

Do you see bands of colors? I see mostly pale orangeish bands, but they’re vibrant enough that I actually opened the GIF in Photoshop to make sure the color isn’t actually there. The effect is known as the Fechner color effect, sometimes also called subjective color.

In the years since Benham originally introduced his spinning toy, variations on it have been used in elementary school science classes and many science explainer YouTube videos, so there’s a good chance you’ve seen this before.

James Butterfield wondered if this phenomenon could be used on television. He worked with a doctor named Derek Fender to figure out what type of flashing patterns would trigger specific colors. Then he worked on building a device that would capture those patterns in a TV camera so they could be displayed on a TV screen instead of a spinning disk.

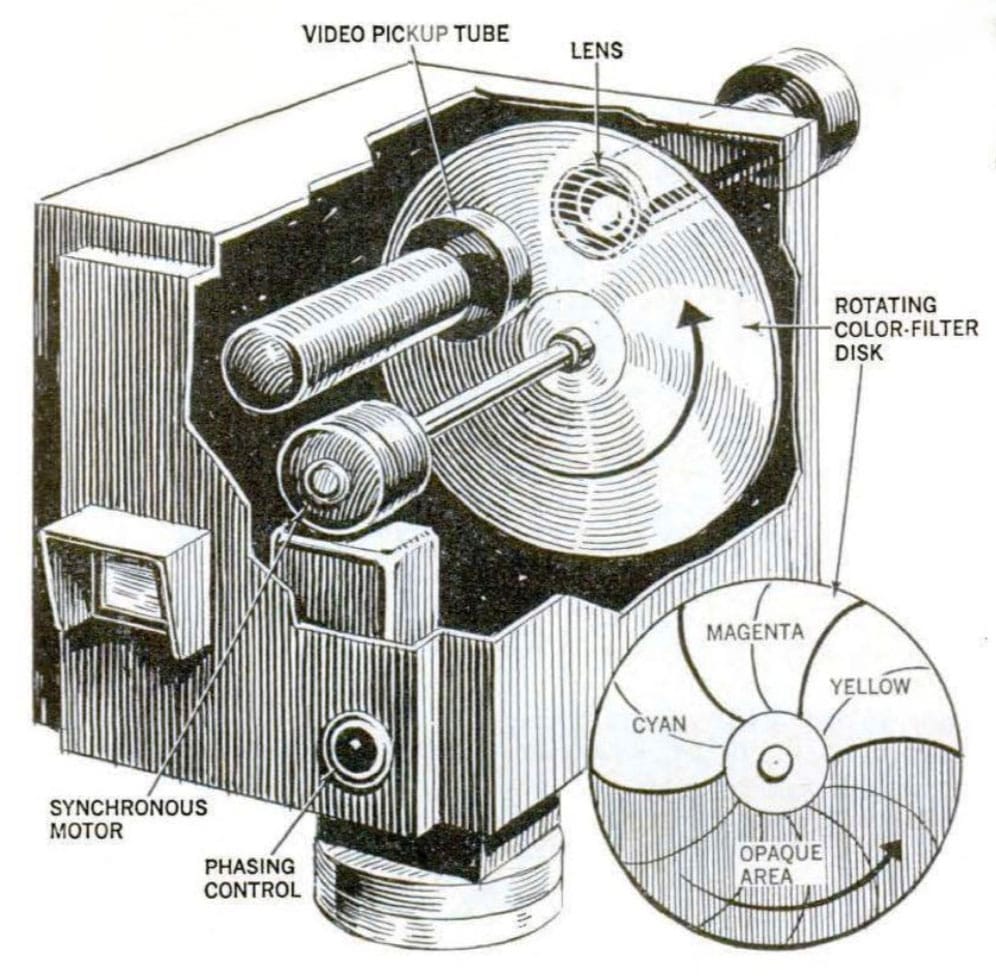

He called his device the Color Translator, a camera attachment with a sort of variation on a Benham disk that spun in front of the camera lens. Half of it was black, and the other half was divided into yellow, magenta and cyan filters. It spun in sync with the camera’s shutter, so when an object is filmed through the Color Translator, you would end up with a sequence of frames like this:

When played back, the illusion of color appeared:

Butterfield wasn’t the first person to apply this phenomenon to a movie or video camera, but his implementation was the simplest. An earlier inventor patented a method that used special film. Butterfield’s Color Translator could work with any camera.

In 1968, a Squirt soda commercial using this process was broadcast in Los Angeles. Instead of promoting it as anything special, it ran with no announcement, to see how people would react. According to an article from Popular Electronics:

Within hours of the electronic-color broadcast, thousands of viewers began asking the same question, “What happened? Did I really see color on my black-and-white receiver? Or am I having hallucinations?”

Other magazines published letters from viewers with statements like, “Is it possible to pick up color TV on a black and white set? I SWEAR I saw a Squirt soft-drink commercial in color” and “It knocked me for a loop...the letters S-Q-U-I-R-T looked greenish or light turquoise.”

But it was also reported that while some viewers saw saturated color, others saw only one or two colors, and some people saw no color at all. So it wasn’t very reliable.

The original Squirt commercial seems to be lost to time. But there was a short BBC report on the technology that you can watch on the Internet Archive.

It explains the technology, and shows some additional examples, like this animation of cereal being poured from a box into a bowl:

They also offer some suggestions to strengthen the effect: “If you didn't see it, it could be because your viewing conditions aren't right. The people who made that film say the curtain should be drawn and the lights on in your room.”

Here’s one more example:

The BBC examines that one frame by frame:

The black pictures are called the discharge pictures because they prepare you for the cycle to repeat itself. The other ones are called the color-creating picture, and the intensity of the color can be varied by altering the number and the sequence of the color-generating pictures separated by the discharge pictures.

Doing research for this, I found a surprising number of people saying they had faint memories of the Squirt commercial that made them wonder if they had only imagined it. It’s like the opposite of a Mandela effect. It was real, but there’s a mass delusion that it was only imagined.

Actually, now that I think about it, even people who clearly remember the color commercial are remembering something they only imagined.

If you made it this far and I didn’t inadvertently trigger a seizure or migraine, I’m curious to hear from you what colors you see strongest. I definitely see the red, but it’s kinda yellowish. I see the blue, but only if I’m looking for it. It’s a very dark and low saturation blue. And the green? Maybe. Barely. And only if I’m really looking for it. And sometimes it looks more blue than the blue one.

The GIFs I posted above are made from the BBC report. I kept them at the original framerate of 25 fps so they contain all the frames required for the effect, with no blending or frame skipping.

A few interesting places to read more about this TV experiment:

- “Now – Color on Your Black-and-White TV Set” Popular Science, August 1968

- “Color TV – That Isn’t” Popular Electronics, October 1968 [PDF]

- “Tomorrow’s World” BBC One, April 17, 1968 [Video presented by Raymond Baxter]

- “Subjective Color System” - Patent 3,311,699

And that’s it for another newsletter! As always, thanks for reading. I’ll see you next time!

David